The User Experience Problems Of Quadratic Voting

In their seminal book, "Radical Markets," Eric Posner and Glen Weyl introduce quadratic voting to improve (or radicalize) democratic preference voting. They argue that by allowing voters to express preference intensity and introducing a social cost for voters, the vote more accurately reflects the populous opinion on a set of choices.

On March 16, 2022, with Hito Steyerl, DoD and Studiobonn, inspired by Weyl et al.'s idea, we conducted a quadratic vote on the future governance mechanisms of Bundeskunsthalle, a federally-backed art exhibition hall. To allow audience participation, we handcrafted strikedao.com (source code), a minimum viable quadratic voting app. Livestream recording on YouTube.

Having been the main developer behind the application, and since I'm currently studying Weyl et al.'s book, with this post, I'll name several conceptional user experience problems we ran into during implementation.

Before I dive in, however, if you want to educate yourself on quadratic voting, I recommend looking at RadicalExchange's concept page on quadratic voting as I won't really go into explaining how it works.

Problem #1: A Social Cost For Voting Isn't Intuitive.

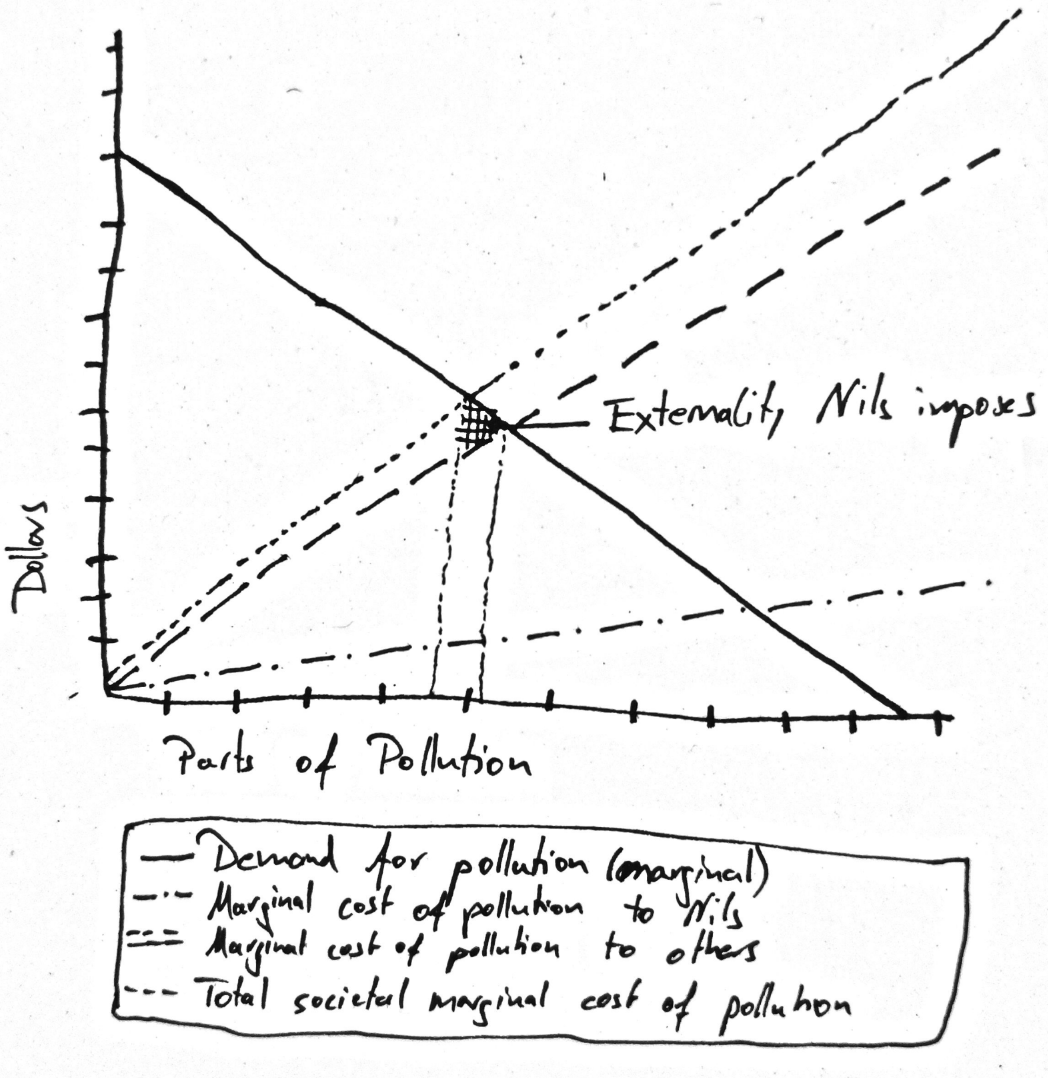

In their 2018 book, Weyl et al. introduce the benefits of having a social cost by telling the story of a town and its nearby power plant emitting pollutants into the air. Their argument: Depending on the individual's intensity of preference, a cost should incur for how much they each demand the plant's pollution to decrease assuming everyone's electricity bills dropping.

For example, in a town with many pollution-tolerant citizens that prefer cheap energy, Nils, who is running a laundry and is strongly anti-air pollution, shall bear the (quadratic) cost of change in relation to his peers. Said differently, he should pay the nominal economic cost of his peers' higher electricity bill that would result from lowering the town's pollution.

While, actually, this example motivates the point for introducing a social cost to preference voting well, I'd say it's much harder to grok in real-life voting scenarios.

Not only isn't it always possible to directly identify a concrete economic cost for each proposal in a voting process, but also, if we'd vote only on choices with perfect information, we may not have to vote in the first place. Things would just take care of themselves.

My point being that preference voting on choices isn't always easily reducable to a nominal economic problem. Particularly not these days.

Learning to differentiate between "voting credits" and "votes" is hard.

However, here's where I see the first actual user experience problem with quadratic voting: Introducing "voting credits" and mapping them onto votes through a mathematical function is where we abandon many.

In my personal experience, asking people to "forget" all about voting and then introducing "voting credits" that only become votes after running them through a quadratic cost function is a huge challenge. Honestly, and without wanting to sound rude, most people probably have long forgotten what a quadratic function looks like or that it's just a more elegant way of saying: We're going to square some numbers. Those school days have been a while back...

But additionally, I want to stress the difficulty of motivating the introduction of "voting credits" - which even I am having trouble understanding at times. The problem is only exemplified by the backwardness of math itself.

The Math Of Quadratic Voting is Literally Backward

As humans of the twenty-first century, we're well-versed in allocating budgets and spending "credits" everywhere. E.g., if we have 5€ in our wallets, we are easily capable of spending them on one espresso, one cappuccino, and one piece of cake - if all those end up costing roughly five euros.

But with quadratic voting, and since we're used to having natural numbers as voting outcomes, the cost function is reversed. We don't define quadratic voting as:

but instead:

At least that's both what Wikipedia and Weyl's book suggest. Where, e.g., five voting credits simply cannot be allocated as it'd compute to be votes, a floating-point number nobody wants to deal with1.

This subtle difference leads to a lot of confusion in the front end. It's, for example, why some voters may not be able to allocate all their voting credits. Below's why...

Voters May Not Be Able to Allocate All Their Credits

In our show with Studiobonn, we, e.g., had given 25 voting credits to each participant and implemented the above-outlined ("backward") math. However, having three proposals gave rise to voting configurations where voters could not spend all credits. An example of the interface is linked in the tweet below.

In our case, if a user allocated all credits to one proposal, the math worked out in their favor and they'd vote with five. However, if they decided to allocate credits to other proposals partially, then sometimes they ended up having leftover credits they couldn't otherwise spend. Consider where, e.g., a voter allocates as follows:

- proposal A: 3 votes (or )

- proposal B: 3 votes (or )

- proposal C: ...

Now, inevitably since there are only seven more credits left (), and since there's no natural number that can be squared to equate 7 (), this voter won't be able to allocate all their credits according to their intensity of preference.

If they decided to give four credits (or two votes) to proposal C, they'd be left with . Similarly, if they wanted to spend nine credits (or three votes), they'd run out of credits beforehand as .

When working with users of StrikeDAO, I often noticed their confusion around this problem. And while it makes sense thinking through it, it's a real head-scratcher for user experience designers.

Moving on, ...

Quadratic Voting Results Are Hard To Interpret

However, I think the probably best feature of boring democratic elections is the replicability of a one-person one-vote election. If e.g., in Germany, all citizens go voting, we can roughly expect that the sum of all votes is 80 million people - or whatever the latest census number from Wikipedia says.

It's this thing our math teachers tried to hammer into our brains before every exam: Sanity-check your results. If the outcome is beyond stupid, trace back the calculation path to find the error.

With regular voting, sanity checks are easy as most people are capable of adding all proposal results. I mean, unless you vote for Trump - then all bets are off.

Still, with quadratic voting, this way of sanity-checking an election's result has suddenly become a non-trivial math challenge.

First of all, since the election's result is the sum of each voter's credit allocation ran through the square root, and since in additions with square roots, the commutative rule is invalid , I can't find an easy way to interpret quadratic voting results.

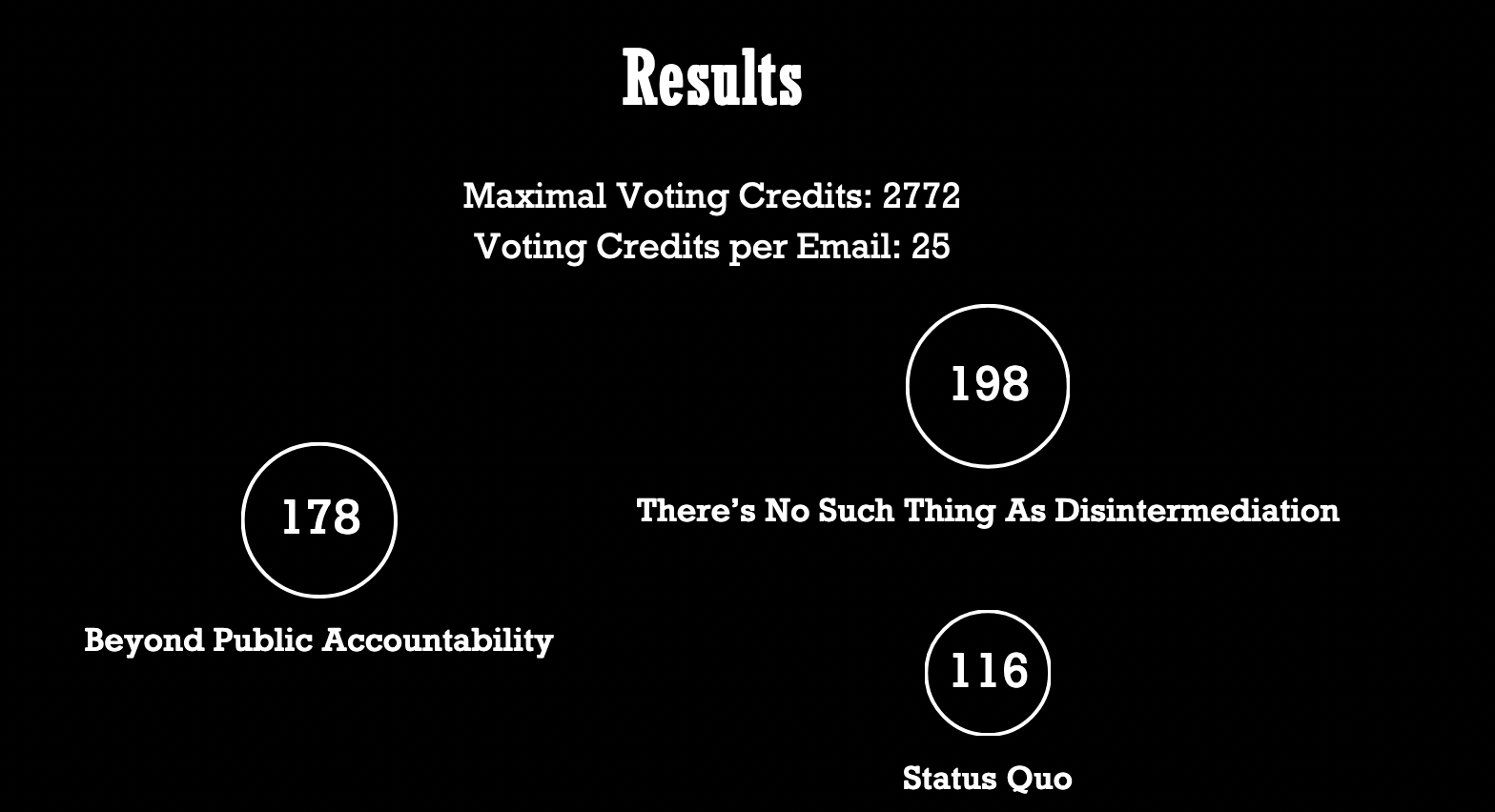

Albeit arguably our design and implementation failure in this regard, what would you conclude from the above screenshot? We can see that "There's No Such Thing As Disintermediation" came in first and "Beyond Public Accountability" second. And more?

In fact, at this point, I'd even consider it a luxury to understand, e.g., "how different people voted": When I see that screenshot, my main question is: Did the vote work out well? Are the results plausible or did someone hack it?

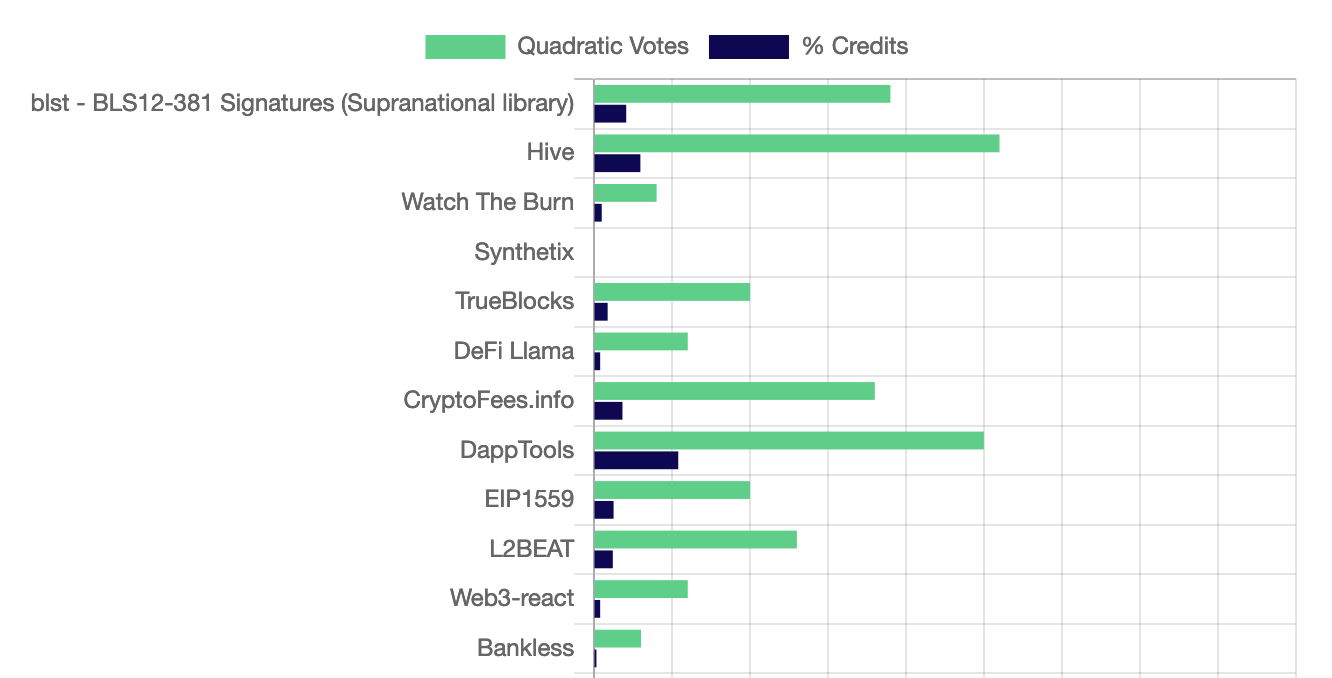

Actually, Anish Agnihotri's quadratic voting app does a better job on this by showing not only the votes but also the percentage of voting credits allocated per choice. However, for reproducibility, I'd argue showing the absolute number of credits would be even better.

Finally, the End Boss: Allocating Voting Credits To Anons On the Internet

Though all of the above are challenging problems, each probably needing weeks or months more research, the real end boss to quadratic voting is properly allocating voting credits. Or actually; the ability to know when one should call their voting app "quadratic."

These days, with edgy mechanisms being rare given the bull market's incentive structure to bubble up innovative ideas, everyone and their dog supposedly implements "quadratic voting."

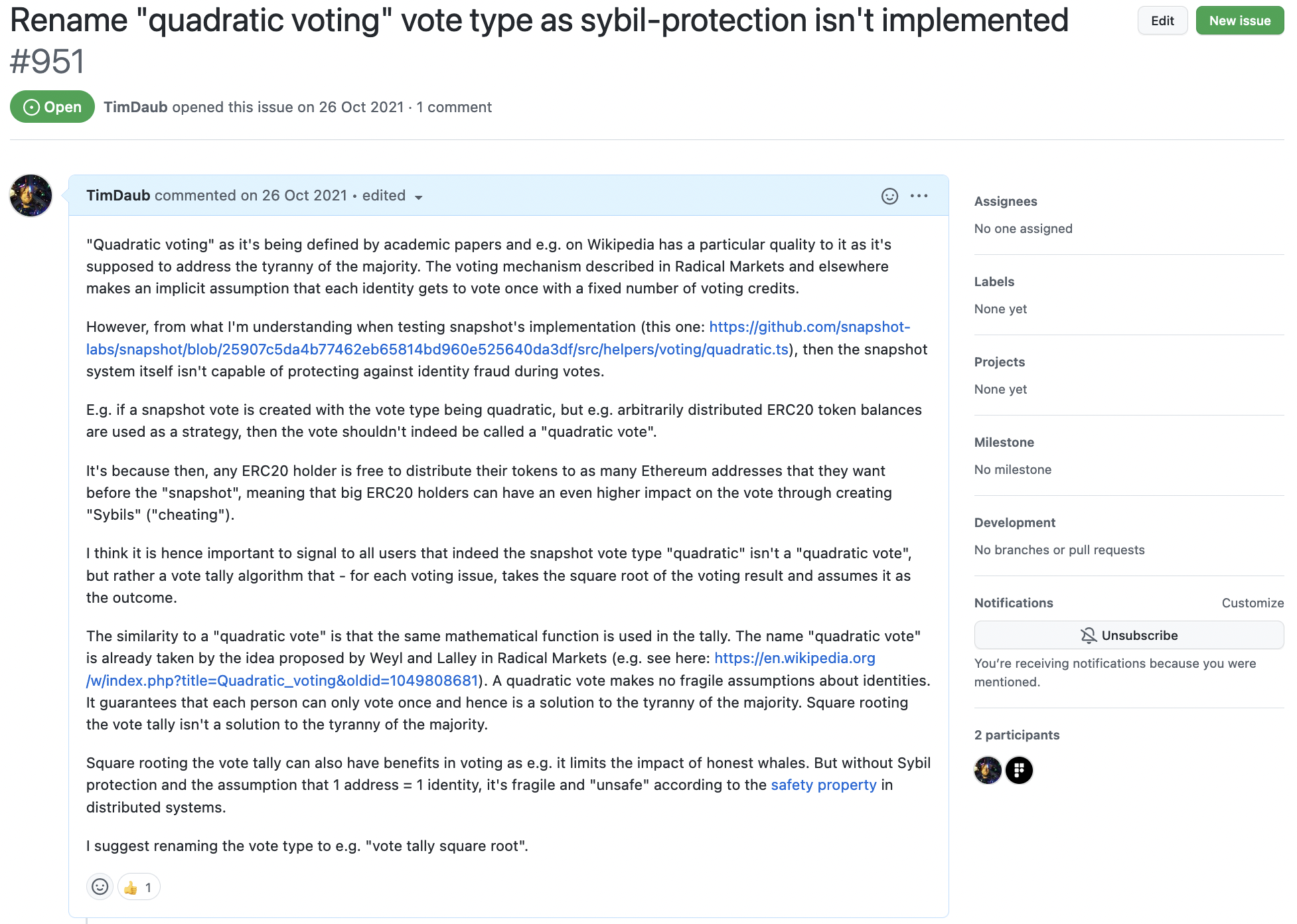

As a popular choice e.g., snapshot.org prominently shipped a mechanism adopted by many for tallying votes quadratically. However, in these announcements, it is often neglected to properly state that quadratic voting is based on the assumptions of mitigating any form of Sybil attacks.

Whereas in a parliament, with a fixed set of representatives having access to a potential quadratic voting app, it poses practically no safety risk: Opening voting to everybody on the internet (as many blockchain governance mechanisms do) has the drawback of introducing a cat and mouse game dynamic.

Since allocating a few credits towards an issue costs less and the margin cost for influence increases, separating voting tokens into many wallets can help to influence one's voting power positively.

It seems, however, that either I'm missing something; or that the others don't fully understand the math behind quadratic voting.

With strikedao.com we ended up having the same problem.

We allocated votes via email, given the flaky assumption that each voter only controls one email on the internet. And while I tried arguing to my colleagues that another layer of verification (e.g., also signing up with a phone number) could make the deciding difference, Hito Steyerl had the conceptually better argument, which was that validation complexity increases quadratically - which is why we (gladly) ended up not quadrupling our validation budget.

Gitcoin now has a flurry of services they want you to sign up for before participating in their grants round. Ocean Protocol uses BrightID, albeit it's entirely unclear how it's supposed to make sure that each human being just ends up creating one identity. Snapshot.org acknowledges its shortcomings concerning tokens and wallets not being Sybil resistant - but still calls their feature "quadratic voting."

Sadly, the world isn't ready for quadratic voting. Actually, the world might still not even be prepared for regular digital voting.

Beyond the minor details I've managed to mention, much more authority carry Tom Scott's videos on why digital voting is generally a bad idea, which are what I want to leave you with. Thanks for reading.

1: "Why Electronic Voting Is a Bad Idea"

2: "Why Electronic Voting Is Still A Bad Idea"

Footnotes:

1: After releasing this blog post, in a reddit post, I was told that spending all credits and dealing with fractional votes is OK. ↑